Olaudah Equiano: The Problem of Identity

Jim Egan

Brown University

When Vincent Carretta argued in “Olaudah Equiano or Gustavus Vassa? New Light on Eighteenth-Century Question of Identity” in a 1999 issue of

Slavery and Abolition that the eighteenth-century author might have been born in South Carolina rather than Africa, as Equiano himself states in

The Interesting Narrative, a scholarly firestorm erupted over the question of this former slave’s place of birth. This is not the first time Equiano’s origins have been questioned. Equiano himself sought to refute claims published in late eighteenth-century English periodicals that he had been born in the West Indies. Such claims were, as Equiano himself knew, aimed at discrediting his narrative and, in the process, the abolition movement with which that narrative was associated. Carretta’s essay, on the other hand, called our attention to evidentiary matters that involve questions of interpretive theory. On what basis, after all, does one determine which instance of writing to consider authoritative when the evidence in these different kinds of sources conflict? Given the fact that Equiano’s narrative plays a crucial role in our understanding of a variety of historical, cultural, and literary issues, and given the fact that where you begin a story helps determine what you can say about that story and what work that story can do, I suppose the furor over Carretta’s claims is only to be expected. After all, is there anyone who would now deny the centrality of the slave trade in all its aspects to the emergence of the modern world? Equiano’s narrative plays a key role in such a narrative, and so his birth takes on special importance.

Equiano, the African: Biography of a Self-Made Man (University of Georgia, 2005) extends Carretta’s research on Equiano’s origins to provide the first scholarly biography in over thirty years of the man known in the Western world for most of his life as Gustavus Vassa. Biographies pose a critical problem for any engaged, thoughtful twenty-first century scholar in that they rely on a notion of identity that has been challenged by a host of critical analyses interrogating the modern emergence of the very idea of the “individual.” Carretta avoids such issues entirely here. Instead, he simply takes modern biographical conventions at face value and uses them to tell the story of Equiano’s life and the development of his distinct and particular identity. Carretta aims, it seems to me, for a more general audience. I want to assess the work, then, in relation to what I take to be his implied audience. Judged from this perspective, Carretta has produced a clear, well-researched, and at times quite interesting biography.

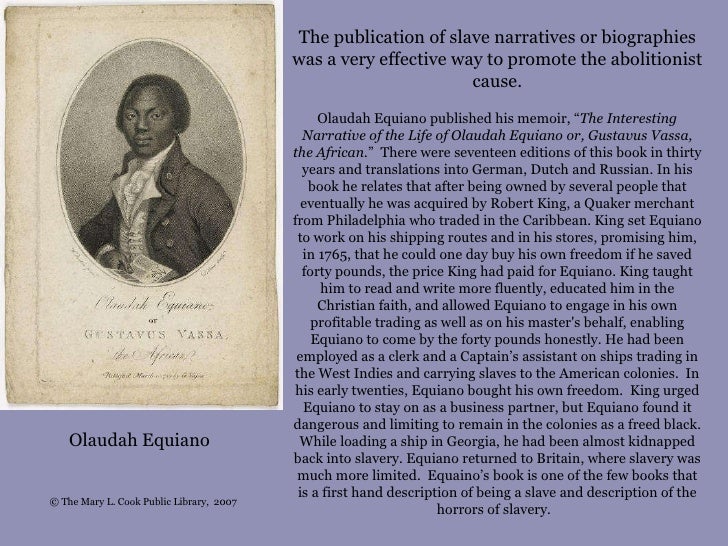

The most interesting and successful chapters were the last three, chapters 12 through 14: “Making a Life,” “The Art of the Book,” and “A Self-Made Man.” These chapters are devoted to the years immediately preceding and following the publication of

The Interesting Narrative. In this section of the book, Carretta provides some insightful, well-argued, readable, and sometimes quite engrossing analyses of, for instance, the significance of the book’s prefatory material, Equiano’s claims to social status, and the engraving of Equiano that accompanies the book. Carretta quite successfully and engagingly situates his analysis of these issues in relation to relevant social and literary materials outside of the book itself. “The Art of the Book” provides the most detailed argument that Equiano might have fabricated an African birth for rhetorical purposes by a rigorous analysis of the chapter where Equiano makes this claim, an analysis that is bolstered by Carretta’s reading this material alongside contemporaneous accounts of Africa, African history as we now know it, and the rhetorical needs and strategies of the abolitionist movement at large of which Equiano was a crucial part. I found his reading quite compelling. In the final chapter, “A Self-Made Man,” Carretta shows us in clear, readable prose the extent to which Equiano worked to promote his book alongside his work on behalf of the abolitionist movement until his death in 1797.

I will confess that I find biographies guilty pleasures—I enjoy reading them even though I am deeply suspicious of, if not overtly hostile to, the theory of identity on which they rely. Who doesn’t want to believe, after all, in the idea of individual identity on which such narratives depend? Unfortunately, I did not find this book to qualify as especially engaging. Given the fact that most of the information about Equiano’s life comes from the now canonical narrative Equiano wrote, a narrative with which my specialty in British-American writing before 1800 has made me quite familiar, Carretta faces a tough challenge with a reader such as myself (and I suspect a number of his readers will be in some position similar to mine). Add to this the fact that Carretta includes long sections of the

Interesting Narrative here, and it is hardly surprising that I found much of the material quite familiar. Nonetheless, I would have expected the story itself to have been more compelling, and somehow Carretta made rather bland the story of a man who escaped slavery to travel around the world, participated himself in the slave trade, produced a book of extraordinary popularity, and participated in one of the major movements that helped change the face of the world in the abolition movement.

I also had certain questions about some key issues raised by Carretta’s narrative. I wondered, for instance, about the amount of agency Carretta grants individuals in the production and/or representation of their subject positions. So, for instance, when he is analyzing Equiano’s writings on Africa, Carretta says, “Equiano chose from the various subject positions available to him the one or ones most appropriate for the particular audience or audiences he is addressing. . . . Skilled rhetoricians know how to shift their positions, that is, how to emphasize different aspects of their identities to best influence and affect their readers or listeners” (256). In making his case for Equiano as a “masterful rhetorician,” Carretta emphasizes Equiano’s conscious intent, his literary choices. The inconsistencies and questions that arise in Equiano’s account of Africa, Carretta suggests, are neither simple mistakes nor flaws in his memory but the result of careful and skillful choices by the author. While I agree that Equiano is an extraordinarily talented writer, the theory Carretta uses above to authorize those skills offers, at best, a rather optimistic vision of individual agency. Equiano may very well have called on various subject positions in his writing of

The Interesting Narrative as a way of increasing or focusing the particular rhetorical power of the book. But to claim such absolute power over a writer’s subject position seems flawed and, as a result, can produce a reading that lacks sufficient thoroughness because one simply fails to see the way in which powers outside the author’s control help produce significant aspects of the text. Were this an isolated instance, I suppose I would have overlooked it, but it was my sense that Carretta’s theory of the subject outlined above operates throughout the book as a whole. What I’ll call, for the moment, Equiano’s “racial” status, for instance, is one that, at least at times, he simply cannot chose to occupy or not. This status, in fact, might be said to inform virtually all of the incidents in his narrative, even those times when he explicitly says it does not or when he fails to mention his “racial” status at all. Or even when the documents make no mention of race. So, for instance, Carretta notes that Equiano “offers the merchant marine a vision of an almost utopian, microcosmic alternative to the slavery-infested greater world” (72). This world, Carretta tells us, “was one in which the content of his character mattered more than the color of his complexion” and where the “demands of the seafaring life permitted him to transcend the barriers imposed by what we call race” (72). I want to applaud several aspects of Carretta’s approach here. First of all, he reminds his reader here and elsewhere of the way in which the category of “race” as we understand it originates during the very period of Equiano’s life, rather than simply being a historically transcendent category. Second, I found his effort to read the material without the presupposition that certain kinds of discrimination or mistreatment on the basis of one’s “racial” status were a given—even if they weren’t mentioned—an excellent approach. Third, his careful attention to the specific language used in the documents he consulted in writing Equiano’s biography I found impressive. In other words, Carretta does not assume that racial prejudice exists when it is not noted.

On the other hand, such an approach might very well miss much of the complex cultural work embedded in the language but not explicitly stated. Carretta suggests that Equiano has such an extraordinary memory and is such a skilled rhetorician, that we can be confident he would have found a way to include any racially charged incidents. Their absence, for Carretta, suggests they did not occur and, as a result, that we should see Equiano’s life in the British Navy at various times as being a place in which racial distinctions did not matter. During these periods, it is as if Equiano is, if you’ll forgive me, just a regular Joe—one of the guys. While I am sympathetic to some aspects of the method Carretta seems to use to portray Equiano in this way, I am quite skeptical that this is an accurate way to narrate the story. In the first place, as even Carretta notes, Equiano’s memory of his life abroad the ship might be faulty. In the second place, Equiano, as Carretta so ably demonstrates elsewhere, might have chosen to omit such incidents for rhetorical purposes. As if this were not enough, even if Equiano implies that he was judged entirely on the merits of his work rather than on his racial identity, we do not have to accept his judgment. Even if he was at times treated as “just-another-sailor,” for instance, he becomes special, unusual precisely for this reason. What makes Equiano special is that he is not treated as special.

I also wanted more discussion of the issues surrounding Equiano’s birthplace. Oddly enough, Carretta seems rather reluctant to explore this issue, or even to be especially forceful in making his argument. Indeed, Carretta’s provides enough qualifications that it can hardly be called an argument. He says on more than one occasion that we will never be able to know for certain for his subject was born, and he notes that while he has raised “reasonable doubt” about what Equiano claims about his birth in

The Interesting Narrative, “reasonable doubt is not the same as conviction” (xv).

In spite of these qualifications, Carretta shows great analytical skills in his discussion of the possible rhetorical benefit of Equiano’s invention of an African birth. He carefully and insightfully examines the first chapter of the narrative where Equiano discusses Africa, and he situates this chapter in relation to other writings of the time with a power and clarity that are quite impressive. Equiano’s masterful invention of an African birth, Carretta argues, demonstrates that Equiano’s “literary achievements have been vastly underestimated” (xiv). “If nothing else,” Carretta tells us, he “hope[s] that

Equiano, the African: Biography of a Self-Made Mandemonstrates how skillful a writer Equiano was” (xv). But surely more is at stake in claiming that Equiano “invented” rather than “reclaimed” an African identity than our evaluation of the literary talents of a particular individual? As I mentioned above, Carretta’s argument for an American birthplace relies heavily on baptismal records and ship’s registers. While he spends about a page demonstrating that the person whom he identifies as Equiano is, in fact, him and, then, explaining that Equiano could very well have listed an African birthplace, he tends to

read these documents with less care than he does

The Interesting Narrative. To be sure, a baptismal record and a ship’s register represent different kinds of writing than a spiritual autobiography. Nonetheless, they too must be read. So while Carretta rightly points out that other analysts have often treated Equiano’s story in his book as a kind of transparent recollection of his life while considering the baptismal records in need of a thorough reading in order to be properly understood, Carretta reverses this interpretive strategy by taking the documents as having little rhetorical content worth reading.

In addition to reading the “non-literary” materials in a more literary way, I would have liked Carretta to explore more thoroughly the implications of relying on one kind of evidence rather than another. He writes, “[a]nyone who still contends that Equiano’s account of the early years of his life is authentic is obligated to account for the powerful conflicting evidence.” While I suppose this is true, his approach to the problem he has raised left me wanting more. How might the elevation of Equiano’s literary status, I wanted to know, change the way we tell, say, the literary histories of the United States and/or Great Britain? Might the change in birthplace alter the way we tell Transatlantic history more broadly? Or the history of modern race-based slavery? I would have appreciated a more thorough discussion—indeed, any discussion—of the disciplinary and institutional implications of accepting Carretta’s argument or not. Why is it that people have reacted so passionately to the notion that Equiano might have fibbed about where he was born in

The Interesting Narrative? What does such debate indicate about the stakes involved in telling the life story of an eighteenth-century slave turned author? Perhaps Carretta failed to include such material because the imagined audience for this book would, in his and/or the publisher’s view, be uninterested in such issues. I think this is untrue. What could be more compelling and current than the question of the implications of where a man whose identity we now call “black” was born? From my view, at least, the problems Carretta’s book raises about Equiano intersect directly with questions and issues I see debated quite frequently as I flip by the Fox News Channel and skim through

The New York Times

.

Equiano's mention of the slave woman wearing the muzzle is brief, and his

reaction is straightforward ("I was much shocked and astonished . .

."), but the purpose is clear. How can a civilized audience hear of

such atrocities and not be equally shocked and horrified? He mentions the

daily starvation and suffering of other slaves; he speaks of dreadful

punishments (men are beaten, burned, hanged, and "staked to the ground, and

cut most shockingly, and then his ears cut off bit by bit" - 773). Equiano

imagines the effect of these details on his audience, and thus, he begins

chapter 6 by informing the reader that he will not spend any more time detailing

the torture of slaves "so frequent, and so well known . . . that it cannot

any longer afford novelty to recite them" (774).

.

Equiano's mention of the slave woman wearing the muzzle is brief, and his

reaction is straightforward ("I was much shocked and astonished . .

."), but the purpose is clear. How can a civilized audience hear of

such atrocities and not be equally shocked and horrified? He mentions the

daily starvation and suffering of other slaves; he speaks of dreadful

punishments (men are beaten, burned, hanged, and "staked to the ground, and

cut most shockingly, and then his ears cut off bit by bit" - 773). Equiano

imagines the effect of these details on his audience, and thus, he begins

chapter 6 by informing the reader that he will not spend any more time detailing

the torture of slaves "so frequent, and so well known . . . that it cannot

any longer afford novelty to recite them" (774).

.jpg)

y:

y: